The evolution of interoperability (part 1)

This is the first post in a two-part series on the evolution of interoperability. Read part two here.

In life, change is inevitable, and history is invaluable. Both are equally true for healthcare interoperability.

As I discussed last time, interoperability is a social construct, constantly evolving as technology, regulations, and community expectations advance. What fits the mold of interoperability today may be deemed insufficient in just a few years. With today's post, I'd like to look at the historical side of interoperability.

Despite the concept's relatively recent buzz, interoperability has existed in some form or fashion for decades. That isn't to say it has been robust or pretty or efficient—it is, on the whole, still not that way—but it's been there, and there's been a dedicated community of passionate people working to make it better. With a focus on the US, and with the caveat that I won't be able to do justice to everyone or everything, let's highlight some of the key milestones in the evolution of interoperability.

Rise of the acronyms

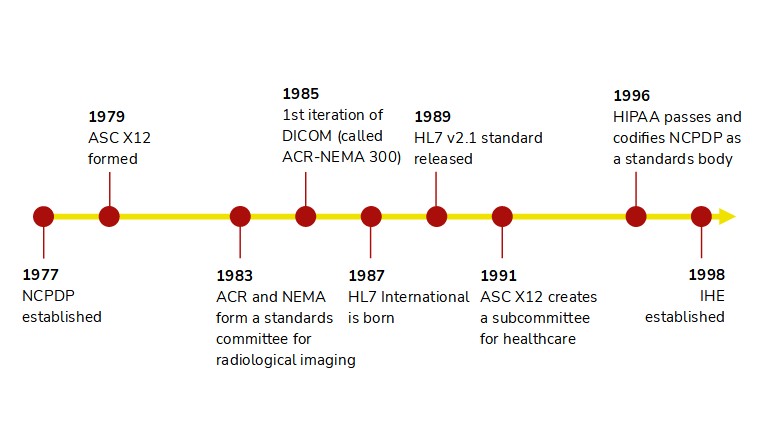

The 1980s and 90s were the metaphorical baby boom of interoperability.

- HL7 International was founded in 1987 and quickly followed up with the first interface standards, HL7 v2.1. Over the ensuing three-plus decades, HL7v2 has developed into likely the most widely supported standard in healthcare IT.

- In similar fashion, the Accredited Standards Committee for X12 began to focus on healthcare workflows in 1991 with the formation of the X12N Insurance Subcommittee. By the turn of the century, X12 was fully aligned with HIPAA and to this day is the standard for healthcare financial operations such as insurance claims and eligibility.

- DICOM was even earlier, published under the name ACR-NEMA 300 in 1985 and rapidly improved upon throughout the next 15 years. Notably, DICOM underwent a shift in 1995 to be inclusive of all medical imaging, not just radiology, which enabled it to expand into cardiology, endoscopy, and dermatology.

- The National Council for Prescription Drug Programs, in existence since 1977, became an accredited standards body in 1996. NCPDP is best known for the SCRIPT standard that facilitates e-prescribing, though it maintains numerous other standards, such as ones for prescription drug monitoring programs and communication between pharmacies and insurance companies.

- And while not a standard, Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) was born in 1998 to help define how technology standards can satisfy clinical workflows. IHE profiles answer the question of "How?" in healthcare interoperability by applying technical specifications to healthcare-specific use cases.

The parallels among these veteran standards say a lot about how interoperability has been viewed historically. For one, interoperability has been use case-specific. Standards bodies aligned around specific workflows and stakeholders, rather than seeking to be something for everyone. DICOM lives and breathes imaging, while X12 sticks to financial operations and NCPDP SCRIPT dominates anything associated with retail prescriptions. Secondly, integrations were predominantly event-driven and followed a publisher-subscriber model. For example, the vast majority of HL7v2 interfaces operate under the premise of "something (e.g., a new patient admission) happened in system A, and that's my trigger to send the details to system B." We'll see later how APIs provide a completely different paradigm.

Finally, these integration methods take an incremental, point-to-point approach to interoperability. Establishing an HL7v2 or X12 connection traditionally means connecting to specific IP addresses and ports for communication over TCP/IP. (There are alternatives, such as exchanging messages over web services, but these are less common.) If you need to secure the data transfer, you set up a VPN between the parties. All this friction limits the potential for scalability, and that's why there is no nationwide HL7v2 network for an app developer to tap into today. This makes sense to an extent because these standards came of age when technology was much different—in the 80s and 90s, the World Wide Web was much less trafficked and its underlying technologies were still nascent. Remember, the year HL7 v2.1 came out, General Motors topped the Fortune 500, the Berlin Wall fell, and Mark Zuckerberg turned five.

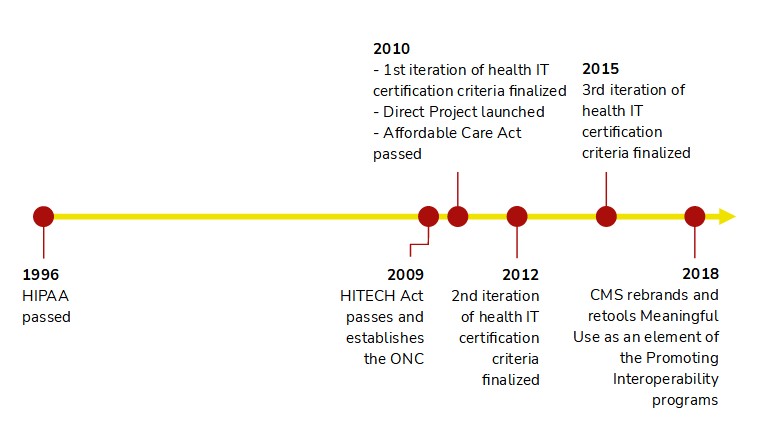

The Meaningful Use era

The HITECH Act of 2009 transformed the US health IT landscape, though its impact on interoperability was gradual. The first iteration of the ONC's Health IT Certification program (which aligned with Meaningful Use Stage 1) focused largely on getting providers onto electronic systems and ensuring they were checking boxes and filling in fields. There were requirements to electronically exchange lab results, immunizations, reportable conditions, and prescriptions, but the final rule removed mandates for electronic insurance eligibility queries and claims submission due to their administrative, rather than clinical, nature. Certified EHRs also needed to electronically receive and transmit patient summaries.

The 2014 certification criteria brought the endorsement of Direct messaging, which is akin to secure email, as a way for providers to safely send clinical information. This was particularly relevant for transitions of care, such as when a patient is referred to a specialist and the referring provider needs to transmit a clinical summary. This is a noteworthy moment because it signals a shift in thinking towards interoperability through networks, rather than through point-to-point connections. Rather than a referring provider needing to establish a connection with every possible specialist, she can use a provider directory, which is like a phone book, to look up the recipient's Direct address and route the documentation correctly.

In 2015, the ONC again signaled a shift. Certified Health IT would now need to allow patients to connect their health data to any app of their choosing via APIs. Here was the federal government finally promoting modern integration technologies that the broader tech community had been using for over a decade. Here was the federal government saying "Patients call the shots. They can use whichever third-party software they would like to surface their health data."

Note, however, all the things this regulation didn't do. It didn't require the APIs to follow a standard, such as FHIR; it didn't require APIs that could write data to the patient's health record, only ones that could retrieve data; it didn't apply to any stakeholders or workflows outside of a single patient requesting their own data; and it didn't require support beyond roughly two dozen data points, known as the Common Clinical Data Set. Additionally, the rules would only apply to EHRs and not to other repositories of health data, such as payer databases. This was merely a starting point.

Catching our breath

We've traversed a few decades in about 1,000 words, so let's recap. We've seen how interoperability really started to emerge in the 1980s and 1990s, thanks to smart people creating and nurturing standards through accredited organizations. These tried-and-true standards rely on the technology of the times, which favors event-driven integration workflows through individual connections, making it difficult to rapidly scale. Interoperability was about how business entities exchanged data, with little input or involvement from patients, and different use cases utilized different standards.

Yet about a decade ago, the federal government introduced key regulations that hinted at a new direction, one built around integrating through networks, leveraging APIs, and transferring control to patients. We are now in the 2010s, and next time I'll cover the most recent advancements. We are not at the beginning of the end of interoperability's evolution—but it is perhaps the end of the beginning.

---

Photo by Eugene Zhyvchik on Unsplash